Throughout the 2024 U.S. presidential election campaign, observers spent much time puzzling over why voters seemed to be so unhappy with the economy, even when macroeconomic data—and most economists—suggested that the economy was historically strong.

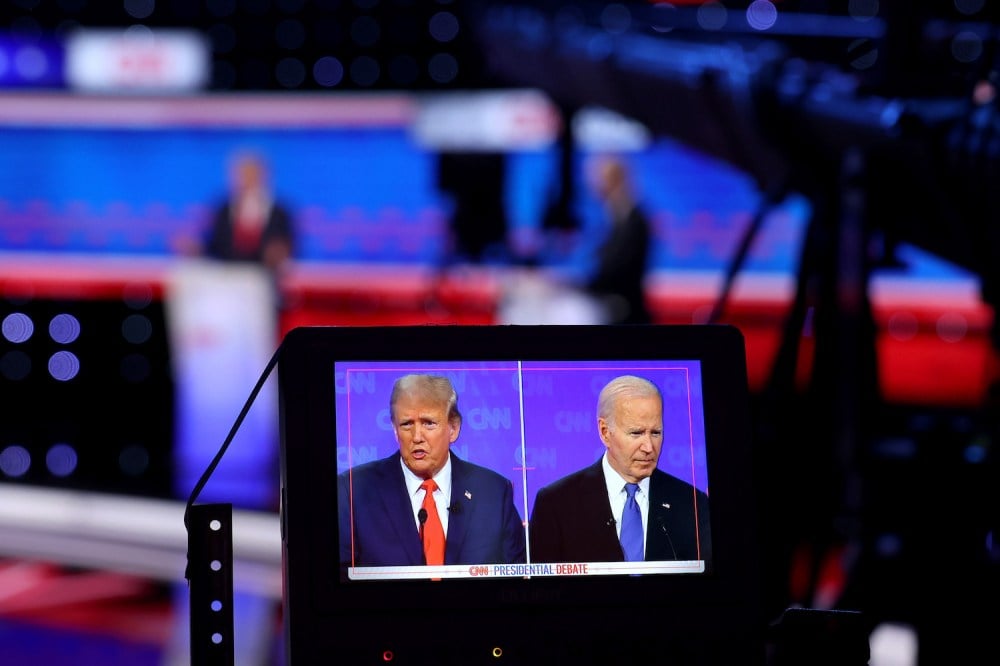

The United States was growing at nearly 3 percent (faster than it had for decades); unemployment (at under 4 percent) was at historic lows; the stock market was at a record high after the best two consecutive years this century; manufacturing jobs were coming back, and inflation—which had surged during the COVID-19 pandemic—was back down to near target levels. The U.S. economy was in many ways the envy of the world, and yet 77 percent of the public believed it was “poor” or “only fair,” which now-President Donald Trump both encouraged and took advantage of.

Throughout the 2024 U.S. presidential election campaign, observers spent much time puzzling over why voters seemed to be so unhappy with the economy, even when macroeconomic data—and most economists—suggested that the economy was historically strong.

The United States was growing at nearly 3 percent (faster than it had for decades); unemployment (at under 4 percent) was at historic lows; the stock market was at a record high after the best two consecutive years this century; manufacturing jobs were coming back, and inflation—which had surged during the COVID-19 pandemic—was back down to near target levels. The U.S. economy was in many ways the envy of the world, and yet 77 percent of the public believed it was “poor” or “only fair,” which now-President Donald Trump both encouraged and took advantage of.

While there were many reasons for this striking perception gap, the best explanation seems to be the unique role of inflation: Unlike broad macroeconomic trends that show up mainly in headlines, people experience inflation directly and several times every day, when filling up the gas tank or buying a sandwich causes sticker shock and anger for which political leaders must be to blame.

Whatever the reason, what got less attention during the campaign was the fact that a similarly striking gap existed between the United States’ actual strength and standing in the world and the perception that voters had of it.

Trump told voters a story of U.S. weakness and global decline, and Americans seemed to buy it, with just 33 percent of those polled in a February 2024 Gallup survey saying they were “satisfied” with the position of the United States in the world today—a level 20 points below what it had been four years previously..

What they apparently failed to see was that notwithstanding the wars in Ukraine and Gaza—and indeed, in some ways because of them—the United States was in a stronger geopolitical position than it had been for many years or even decades, in stark contrast with the perception of weakness and decline.

Compared with both its allies and its adversaries, the U.S. economy is in anything but decline. U.S. economic growth over the past 20 years has dwarfed that of other wealthy countries, a gap that has grown over the past few years to the point that the U.S. economy is now nearly twice the size of the eurozone and almost seven times that of Japan. Meanwhile, China’s 30-year run of meteoric growth seems to be ending with its economy bogged down by low consumption and a bloated property market, while Russia’s economy has been devasted by sanctions, export controls, and war.

The United States has real economic problems—including debt, stubborn inflation, and inequality—but its share of the global GDP, at around 26 percent, is higher than it has been for nearly two decades and similar to where it was at the end of the Reagan administration. That economic power remains the basis for exercising unparalleled global influence.

Virtually every other measure of relative power underscores U.S. global strength. Far from artificially constrained in the name of climate change, as alleged by critics, U.S. energy production is at an all-time high, with the country leading the world in production of both oil (20 percent of global production) and natural gas (25 percent). U.S. technology companies—such as Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, and Tesla—dominate global markets, and the country remains well ahead of its allies and competitors in the field of artificial intelligence. The U.S. dollar remains the currency of choice for nearly 60 percent of international transactions and currency reserves—giving Washington unique power to leverage sanctions, freeze assets, and take advantage of deficit spending. Demographically, the United States is also better positioned than competitors, with a higher birthrate than any other advanced industrialized economy or adversaries such as China or Russia.

American voters in 2024 may not have been feeling good about the country’s standing in the world, but people elsewhere were: Even in summer 2024, amid rising global criticism of U.S. policy in the Middle East, a Pew poll of 34 countries from all over the world showed that international views of the United States were still strongly favorable (54 percent favorable vs. 31 percent unfavorable) and that twice as many people surveyed had confidence in President Joe Biden to do the right thing than they did in Chinese President Xi Jinping or Russian President Vladimir Putin—or Trump.

In other words, Americans had the impression that a strong majority of people around the world (57 percent vs. 42 percent, according to a February 2024 Gallup survey) viewed the United States unfavorably, when the reality was the other way around.

The U.S. geopolitical position in key regions of the world also belies the notion of decline. In Europe, the war in Ukraine has certainly been costly and has no doubt contributed to the American perception of foreign-policy failure. In fact, the response to Putin’s invasion was a remarkable demonstration of U.S. power. In February 2022, virtually all observers thought Russia would take Kyiv in weeks. Instead, finances and weapons from the United States and other allies helped Ukraine thwart the invasion, and the country remains free and independent, while Russia has lost some 700,000 dead and wounded on the battlefield and is forced to rely on North Korea for reinforcements.

With the addition of Finland and Sweden—and European defense spending rising considerably since the Russian invasion—a U.S.-led NATO is now bigger and more unified than ever. If Trump ends U.S. military support for Ukraine, alienates NATO allies (with initiatives such as unilateral tariffs or his threatened attempt to acquire Greenland), or pulls out of the NATO alliance altogether, U.S. influence there will obviously diminish; but he inherited a position of strength.

The United States’ strength and standing in Asia is also enviable. When the Biden administration took office, it seemed to be a matter of “when,” not “if,” China’s economy would surpass that of the United States, and fears about Beijing’s domination of the South China Sea or a military takeover of Taiwan were high.

Instead, China’s post-COVID-19 recovery has been anemic—leading Beijing to seek more stability in relations with the United States—and Washington has bolstered its extensive network of alliances around the region. Targeted U.S. export controls, tariffs, and investment restrictions have constrained China’s military rise while Washington has bolstered political and security ties with Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, Singapore, Australia, Taiwan, and others.

Trump could, of course, squander Washington’s leverage and influence if he repeats calls to pull U.S. troops out of South Korea or questions the country’s willingness to defend Taiwan, but those would be self-inflicted wounds.

Finally, for all the chaos in the Middle East—no doubt itself responsible for the impression of U.S. weakness—Washington’s geopolitical position in the region is now stronger than it has been for decades. The war between Israel and Hamas, which has caused mass civilian casualties and destruction, has been painfully tragic, and strong U.S. support for Israel has alienated Arab populations across the region.

At the same time—and in part thanks to that support—the strategic situation in the neighborhood has been positively transformed. The United States’ main regional adversary, Iran, is now believed by many to be weaker than it has been since its 1979 revolution, and its proxies—including Hamas and Hezbollah—have been decimated. Iran’s ballistic missile program, once a core element of its deterrent, has proved to be ineffective and its air defenses have been revealed as weak. Tehran also lost its main regional partner with the fall of the Assad regime in Syria.

The U.S. military’s demonstration in April 2024 and October 2024 that it—along with a coalition of regional partners—could shoot down hundreds of ballistic missiles and drones launched from Iran toward Israel was a powerful reminder to the entire region and beyond of the benefits of having the United States on your side. Trump is certainly inheriting a complicated regional picture in the Middle East, but he is also inheriting a historic opportunity.

None of this is to say that the United States does not face enormous challenges or rivalries on the world stage, including China, Russia, North Korea, and Iran. But the notion that the past four years revealed the United States to be a paper tiger—or that it is now in a weakened global position compared with any of its rivals—is absurd.

If Trump reverses the bipartisan policies that led to this position of strength—the creation and maintenance of alliances; an open U.S. economy; an investment in soft power (including through development assistance); upholding defense commitments; and a willingness to confront international aggressors and stand up for global rules and norms—then he could end up producing the very decline and insecurity that he falsely claims to have inherited.