As American foreign policy hinges more and more on the gut instinct of one person—President Donald Trump, of course—it’s tempting to wonder how policymakers from a previous generation might think about the White House today. Would Henry Kissinger have preferred a smaller National Security Council, for example? But surely, a figure of his stature and media savviness would have clashed with the current occupant of the Oval Office?

While there are several tomes on Kissinger, his contemporary and sometime rival, Zbigniew Brzezinski, has not been profiled as much. The journalist Edward Luce seeks to change that in his new biography, Zbig: The Life of Zbigniew Brzezinski, America’s Great Power Prophet, which draws on remarkable access to personal diaries and letters to recount the life of one of the great figures in U.S. foreign-policy history. I spoke with Luce on this week’s FP Live about Brzezinski’s life, legacy, and how he would gauge geopolitics today.

Subscribers can watch the full discussion on the video box atop this page or follow the FP Live podcast. What follows here is a condensed and edited transcript.

Ravi Agrawal: So, why did you choose to write about Zbigniew Brzezinski?

Edward Luce: Well, partly because his family came to me with the diaries that he kept when he was [U.S. President] Jimmy Carter’s national security advisor. They were spoken into his Dictaphone every night in perfectly formed paragraphs and dealt with these extraordinary events that happened in that very geopolitical decade, the 1970s. There was the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the Camp David agreement, which was the first time an Arab country—Egypt—had recognized Israel. There was the treaty returning the Panama Canal to Panama, the Soviet non-invasion of Poland, the normalization of relations with China, and the Iranian hostage crisis. This is a gripping first draft of history.

RA: Tell us about his early life. He comes to Canada at 10 years old, but in many senses, he is still very much shaped by what’s going on in Europe.

EL: I got schoolbooks, yearbooks, from his early years in Canada. He was born in Warsaw in 1928. Then this non-English speaker washed up on Canada’s shores. And by 1940, at the end of his first year, he wins first prize in English and English poetry in an Anglophone school. In the yearbook, all the kids are asked to list their favorite activities. They write things like yawning, teasing my grandmother, kicking a football. And Brzezinski puts Europe. This is early into World War II, after his home country of Poland had been incinerated. He had left only a year earlier, after the notorious Munich agreement between [British Prime Minister Neville] Chamberlain and [Nazi leader Adolf] Hitler, which gave away the Sudetenland to the Nazis. In the first few weeks of the war, Brzezinski would listen to Radio Warsaw every night. It went silent after a couple of weeks, except for the first 11 notes of “Polonaise” by Polish composer Chopin. And one night, that was replaced by “Deutschland über alles,” which was like a guillotine coming down.

That sense of wounded Polishness was always present within him; there was always a cavalry charge in Brzezinski’s persona. He would go straight for opponents. There was nothing wily or deceptive about him. The history of Poland and his sense of anguish over a lost nation was really the motivating boost for his life.

RA: And he goes on to write this incredibly important master’s thesis, laying out a road map for defeating the Soviet Union.

EL: There are many complications and contradictions in Brzezinski’s life, but this is a remarkable through line. In 1950, he’s 22 and at McGill University in Canada. He produces this master’s thesis, titled “Russo-Soviet Nationalism,” in which he lays out the strategy that he follows until the end of the Cold War. It’s a remarkable document from a 22-year-old. He learned Russian, but that document is informed by his Polishness because his thesis is that the Soviet Union’s Achilles’ [heel] is the suppressed nationalisms within it. Not just the captive nations (as they were then called) of the Warsaw Pact, like Poland and Hungary, but also the suppressed nations within the USSR. These are the Ukrainians, the Georgians, the Tajiks, the Kazakhs. Brzezinski’s thesis argued that these people did not see themselves as Soviet citizens but as living under a Russian yoke. At that point, Brzezinski was unique in pointing this out. Other Sovietologists accepted that Soviet citizens were Soviet citizens and so treated the Eastern Bloc as a monolith. Brzezinski went on to pioneer the study of comparative communism as a result, which, decades later, is how the Cold War ended.

RA: It has had a profound influence to the present day, if you look at the war in Ukraine.

Ed, that brings me to the 1960s and ’70s, as he moves to the United States. One of the defining figures in his life from then on is Henry Kissinger. Both were professors who craved power. They wanted to go to Washington and become policymakers. They also had a knack for acquiring rich and powerful benefactors. Were such commonalities unique to these two immigrants from Europe, or was there something else in the water?

EL: You’re right. They were both immigrants from the bloodlands of Central Europe. And both reached the highest level you could in American foreign policy for a naturalized American. But they also share something with a very American strategist, George Kennan, the godfather of American Cold War containment strategy. He understood that immersion in the life and language and perceptions of America’s adversaries and allies is important for understanding foreign policy and forming strategy. You don’t have to be an immigrant to think like that. But in my interviews with Kissinger, he did stress they had a sense of the tragic in human events and the fragility of societies in common. Kissinger’s extended family died in the Holocaust, and much of Brzezinski’s perished from Stuka dive bombs and Soviet tanks. They were exceptionalists in believing America was the last great hope. But not in the providential sense. They believed that history went on and on and was full of danger.

RA: Like Brzezinski, Kissinger and Kennan were grand strategists. Theodore Bunzel, in reviewing your book in FP, made the case that the era of the great geostrategist is over. Part of the reason, he argues, is because modern-day foreign-policy advisors spend too much time running a bloated bureaucracy. Do you agree with that assessment? And in your conversations with both Kissinger and Zbig in their later years, did they lament how the foreign-policy sausage now gets made?

EL: Both would have argued that there was no lack of supply of big brains. The problem is one of demand. Washington, as it functions nowadays, has prized foreign-policy entrepreneurship less and has imposed more domestic political tests on people in the foreign-policy field. Think tanks are more conservative and risk-averse, to pass what I call “the Senate confirmation test.” Groupthink, rather derisively labeled “the blob,” is strong. So Zbig and Kissinger would have trouble making their way as they did in the ’60s and the ’70s. In the early Cold War decades, so-called Cold War universities sprung up with massive public-private partnerships to really understand the Soviet Union. They were multidisciplinary, had big budgets, recruited the best and brightest from around the world. I don’t need to belabor what a mirror image that is to the Washington of today.

RA: Brzezinski comes off far better than Kissinger does in your book. Zbig ends up being right on the Soviet Union, on Cambodia, on Vietnam, on Iraq. But Kissinger, of course, is a much more profiled man. As you were writing those sections, how did you think about that?

EL: I tried to tell the story as fairly as I could. In that old Isaiah Berlin test of “are you a hedgehog or a fox?” Kissinger’s a fox: a very skilled practicing diplomat as well as strategist. Brzezinski didn’t practice diplomacy that much. And Brzezinski’s a hedgehog because on the big question of the Cold War, he was correct. It was also Brzezinski’s belief and prediction that the Soviet Union was declining quite rapidly. It had a system of promoting the least innovative, least creative people, which he called reverse natural selection. And he saw it as ossified and run by old men. Therefore, the question was how soon it would collapse and how quickly the United States could make way for that eventuality.

Kissinger was very different. He was quite a pessimist. He thought the Soviet Union was still in the post-Sputnik phase and that it was overtaking, or at least emulating, the United States technologically and therefore should be treated as a permanent feature of a landscape. It should not be provoked. There should be mutual non-interference in each other’s affairs. They had very different Cold War strategies and very different diagnoses of what the Soviet Union was. It’s hard to make any other conclusion except that Brzezinski was right on this.

RA: Iran was widely seen as Brzezinski’s and President Carter’s most important foreign-policy failure. Zbig misstepped in advocating for the U.S. to admit the Shah and for pushing for that disastrous rescue mission to free U.S. hostages. How did he reconcile what happened?

EL: I know from others that he was lifelong embarrassed by his lack of knowledge on Iran. One example of this is when the Shah was admitted for treatment to the United States after he had already been driven into exile by the Iranian revolution. The CIA was quite blind on Iran, so the Americans didn’t even know he had lymphoma. Now, if Brzezinski had known Iranian history, he would have known that the same Shah had been put back on the throne in 1953 by an Anglo-American coup that ousted the elected prime minister, [Mohammad] Mossadegh. So Iranian paranoia had some grounds. Even Carter said, Zbig really badly advised him on Iran. And it’s a function of his ignorance of that region.

RA: Brzezinski was an advocate for stronger U.S.-China ties. In 2009, he wrote in favor of a G-2 between Washington and Beijing to manage global challenges. He was out of step with the hawkish consensus of the time. What would he make of the current bipartisan hostility toward China?

EL: He was critical of what he saw of this, which started before Trump, but increased with him and was sustained under first [former President Joe] Biden and now Trump again. He said that America would bring about the kind of China it feared. He was less zealous on changing what happens behind China’s borders than he was on the Soviet Union. I attribute part of that to his Polishness.

But also, he’d invested a lot in the geopolitical chessboard move of normalization with China. When Deng Xiaoping made the first-ever visit of a Chinese leader to the United States, his first night on American soil was spent not at the White House with Carter but at the Brzezinskis’ family home in McLean, Virginia. He ate food cooked by Brzezinski’s wife, served by his children. You can see great emotional investment there. Kissinger shared that, by the way, and both were treated as massive celebrities in China whenever they visited. And so, Brzezinski would probably stick to his critique.

But even if he shared the bipartisan consensus that China is the primary geopolitical adversary and threat to the United States, he would, of course, question how Trump is addressing that. This declaration of economic war on the world is actually driving entities like the European Union, and even Japan and South Korea, closer to China. That is not a good way of isolating China as a threat. So he’d have tactical criticisms even if he agreed with the consensus.

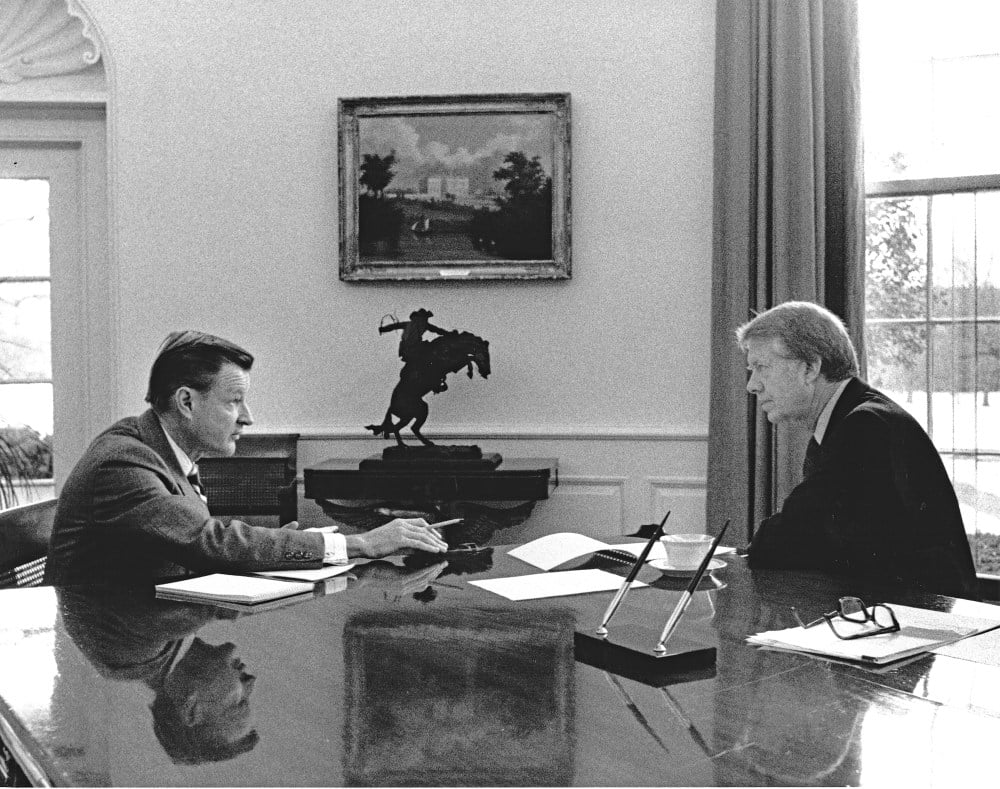

RA: The intimacy and complexity of his relationship with Carter really stood out in your book. How does it compare to how other presidents treated their advisors?

EL: I mentioned that Deng Xiaoping’s first night on American soil was spent at Brzezinski’s. And this is a comment about Carter; how many presidents would permit that to happen? But Carter said, “He’s your friend. You should have him to dinner.”

Each relationship is unique. Theirs was very different to the Kissinger-Nixon one, which had a lot more mistrust. Brzezinski and Carter were closer in age. Unlike Nixon, Carter had no foreign-policy experience, so he relied more on Brzezinski. Carter’s big strategic ideas came from Brzezinski. [President Richard] Nixon had his own big strategic ideas, which Kissinger then brilliantly executed. You’ve got this Polish Machiavellian and this Sunday school preacher, but their relationship was as close and as frank as any presidential relationship with a foreign-policy advisor has been. They would have fights. It was a deeply trusting relationship, but Brzezinski could be rude and remarkably blunt for an unelected advisor talking to his president.

RA: That’s right. He was brusque with everyone around him and not scared to call a stupid idea stupid. He did not suffer fools.

EL: He did not suffer fools. One of the reasons that Kissinger is a bigger name is because he was an absolute charmer. He was the seducer of global proportions. Therefore, he was a celebrity. Brzezinski verbally decapitated people. He had a superpower of not needing to be liked, which is a rare attribute in public life. But it’s also a weakness because people are going to dislike you; a lot of people did.

RA: One of the important parts of the Carter global doctrine was human rights. That endured as a bedrock of both parties’ foreign policy for many years. How would Zbig see America’s turn away from a human rights-based foreign policy?

EL: For slightly different reasons, both he and Carter were very strong on the need to elevate human rights. Remember, this was the first administration that did not inherit the Vietnam War as a problem. So it was the first administration that was able to go on the ideological offensive.

What they inherited was the Helsinki agreement, which gave the Soviets recognition of postwar borders that they’d been craving. And in exchange, the Western Europeans had really insisted on what they called the third basket, which was human rights. Kissinger was uninterested. But Carter loved it and needed very little persuasion from Brzezinski to champion dissidents like Andrei Sakharov and Charter 77 and the Helsinki watch groups, as they called themselves, mushrooming behind the Iron Curtain. Brzezinski saw it as a devastating tactical weapon against Moscow. It helped produce groups like Poland’s Solidarity, which contributed to the downfall of the Soviet Union. On June 4, 1989, the Solidarity party swept the Polish elections and the USSR accepted the results. That’s the day the Cold War ended. It fell several months later, but that day, the Soviets gave up on their monopoly on power. June 4 was also the Tiananmen Square massacre. And Brzezinski counseled Bush Sr. to find ways around it and to resume relations with China. And so Brzezinski had a slightly differential approach to human rights, depending on which part of the world.

If you want to see him as consistent rather than having double standards, I would say he did not see China as having an Achilles’ heel. And largely speaking, China doesn’t. It’s got Tibetan and Uyghur minorities, but the vast share of the population is historically Chinese within relatively historic Chinese borders. And so, he didn’t see regime change as remotely viable. But there’s no doubt about it, he was pragmatic and selective on human rights.

RA: How do you think foreign policy today is either helped or harmed by the lack of a figure like Brzezinski?

EL: I’ve thought about this question a lot. In the early post-Cold War era, Brzezinski wrote a book called Out of Control. This, of course, is the period where there’s quite a spirit of triumphalism in the West and in Washington, particularly. America has won the Cold War mostly peacefully and therefore is the ideological victor. Brzezinski warns in this book that a lot of people feel they’re on the losing side and that these people would form an alliance of the aggrieved with China as the big brother and Russia as the little brother with Iran, North Korea, and others. That alliance of aggrieved was with [Russian President Vladimir] Putin on Red Square in May to celebrate the annual Victory in Europe Day.

He also argued in that book that we’ve moved from a strategic period, focusing on understanding your enemies, to an a-strategic period, where we are telling the world that it should be like us. Washington’s foreign policy sees itself at the apogee of what a society should be, so other countries should be interested in becoming more like us, and if you wish, we will help you get closer to where we are. That caused Brzezinski to plunge quickly from being the relative optimist in the Cold War scenario to being a pessimist.

We say we’re living in the era of the revenge of geopolitics. People need to realize quickly that requires being smart and nimble and thirsty for knowledge about other players in the world. At the same time, Brzezinski’s era was bipolar, but this is multipolar and therefore more complicated and potentially more unpredictable. If people learn this, they might begin to value bigger strategic thinking again.

RA: As much as this is the revenge of geopolitics, it’s also the era of backlash. Backlash against globalization, human rights, trade, open borders. And every time you have a backlash, there’s eventually a backlash to the backlash. Might a new generation of Democrats turn to Brzezinski and his work as the basis for new ways to think about America’s role?

EL: For the last academic year, I was teaching a course at Brown University called “The Revenge of Geopolitics.” These undergraduates had a much flintier mindset than the students I was interacting with a decade ago around this idea that Kissinger and Brzezinski shared: the perfect is the enemy of the good. Do not aim for perfection in foreign policy; aim to avoid disaster. I detected that more realistic, maybe more practical and intellectually curious, mindset, amongst younger Americans. They’re less naive. And who could be surprised by that? If you think of the political and global environment that they came to consciousness in, that should not be surprising. So I have no doubt that in the spirit of thesis, antithesis, synthesis, there will be an antithesis to this. There will be a backlash to what you might call a-strategic thinking, which is a posh word for stupid thinking. And I think I’m picking up signs of it.