Nike’s Jumpman, roses and a popular phrase from a Donald Trump-supporting Puerto Rican rapper: These are some of the tattoos defense lawyers and relatives say helped authorities accuse several Venezuelan men of belonging to Tren de Aragua gang.

The men were not deported to their homeland last weekend but were instead sent to El Salvador, where they were jailed in a notorious megaprison, raising questions about whether they were given due process.

Lawyers for at least five men have said in court filings this week that the U.S. government apprehended their clients in part because of tattoos that immigration authorities believed signaled ties to the gang.

Law enforcement and immigration officials have said in the past they’ve had a challenging time identifying legitimate members of the Venezuelan criminal organization. Often the only information they do have to identify individuals is alleged gang tattoos.

In the case of the recent deportation flights, Robert Cerna, the acting field office director of enforcement and removal operations at Immigration and Customs Enforcement, said in a sworn declaration on Monday that officials did not solely rely on tattoos to identify the deportees as alleged gang members.

But family members and attorneys are contesting that assertion, saying the inkings in question merely indicate the men are sports fans or family men, not gang members. They believe their clients and deported relatives were falsely accused and targeted because of their tattoos, and denied the men are connected to Tren de Aragua at all.

Other Latin American gangs, such as the Salvadoran group MS-13, are known to use certain tattoos to identify their membership.

But that’s not the case with the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua, according to Ronna Risquez, an expert on the group who authored the Spanish-language book “The Tren de Aragua: The Gang That Revolutionized Organized Crime in Latin America.”

Risquez said tattoos are not closely connected with affiliation to Tren de Aragua. When asked if there’s a specific tattoo that identifies Tren de Aragua members, Risquez told Noticias Telemundo, “Venezuelan gangs are not identified by tattoos.”

“To be a member of one of these Venezuelan organizations, you don’t need a tattoo,” she said in Spanish. “You can have no tattoos and still be part of Tren de Aragua. You can also have a tattoo that matches other members of the organization.”

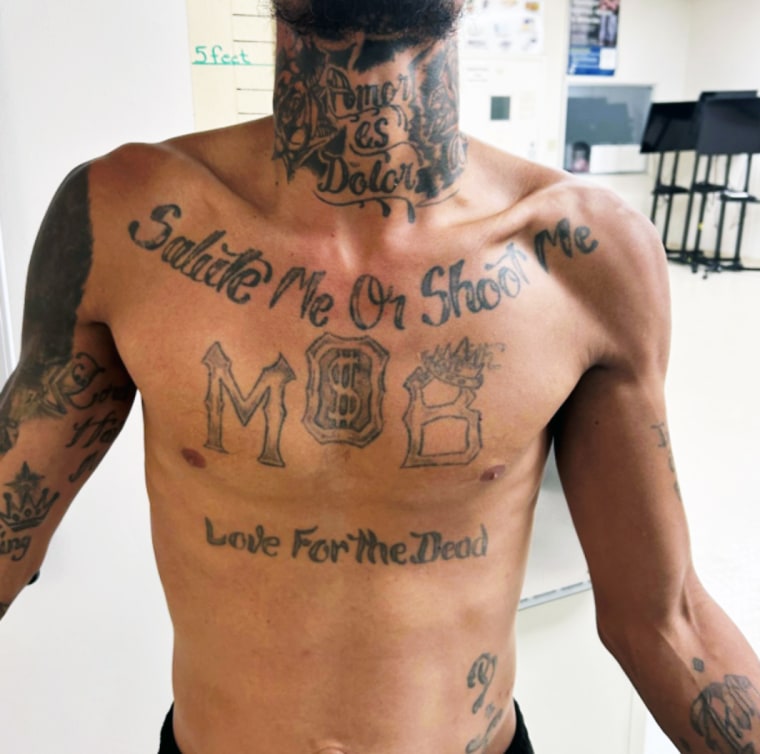

Law enforcement and immigration officials across the nation have linked several tattoos to Tren de Aragua: stars on shoulders, crowns, firearms, grenades, trains, dice, predatory felines, gas masks, clocks, the Illuminati sign and the jersey number 23 — which basketball players including Michael Jordan and LeBron James made famous — in addition to tattoos of roses and the Jumpman logo.

Other tattooed phrases law enforcement says are associated with the gang include “Hijos de Dios” (Sons of God), or its abbreviation “HJ,” and “Real Hasta la Muerte” (Real Until Death).

The government of El Salvador stated this week that hundreds of men deported from the U.S. last weekend were members of Tren de Aragua. In a propaganda-style video, the detainees were shown handcuffed in a crouched position as their heads were being shaved ahead of their transfer to the CECOT megaprison, according to El Salvador’s Press Secretariat.

The video shows some prisoners who have tattoos: One man sports ink of a rose, an Illuminati symbol and the Jumpman logo, inspired by Michael Jordan — all tattoos previously cited by police and immigration authorities as evidence of ties to Tren de Aragua.

But Risquez said that gang members also sport tattoos considered culturally popular at the moment and popular among the general public — such as “Real Hasta la Muerte” tattoos, a phrase popularized by Anuel AA, the reggaeton singer.

“This guy is loved by many Venezuelans and by many Latin Americans who have adopted this tattoo, and they’ve gotten that tattoo,” Risquez said. “So that tattoo can’t be associated with Tren de Aragua because there are many people who aren’t from the Tren de Aragua, including Anuel, who have that tattoo.”

The Trump administration views Tren de Aragua as a national security threat, saying dangerous members have entered the country illegally. In the U.S., law enforcement has accused dozens of people of belonging to the gang in at least 14 states, according to an NBC News analysis.

The administration has repeatedly cited Tren de Aragua as the embodiment of the criminal immigrant as part of the president’s aggressive immigration enforcement agenda, which has included sending hundreds of Venezuelan immigrants to the U.S. naval base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and to the Salvadoran megaprison, as well as stripping hundreds of thousands more of temporary legal status in the U.S.

Targeting Venezuelans because of their tattoos is “wrong and outrageous,” said Bill Hing, a law professor at the University of San Francisco and co-director of the school’s immigration and deportation defense clinic.

“It’s very evident that just having a Michael Jordan tattoo does not necessarily mean that a person is a gang member,” said Hing, who has represented hundreds of asylum-seekers from Central America, Colombia and Venezuela.

A neck tattoo of the Jumpman logo was allegedly among the reasons one man was detained at Guantanamo along with 176 other Venezuelans, according to documents filed in a lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union and other groups.

“Jordan is popular around the world, and for many Venezuelans he’s part of their fashion,” Hing said. He echoed Risquez in saying that most people get tattoos based on pop culture references as well as their geographical or ancestral roots, racial pride and religion.

The idea that a Jordan tattoo or jersey would be used to link someone with Tren de Aragua is close to laughable, said Risquez.

The Department of Homeland Security did not respond to a request for comment. But on Tuesday, the White House said in a statement in response to the deportation flights to El Salvador that it was “confident in DHS intelligence assessments on these gang affiliations and criminality.” It added that the Venezuelan immigrants who were removed from the U.S. had final orders of deportation, though some attorneys and family members of the deportees are contesting that.

“This administration is not going to ignore the rule of law,” the statement said.

Hundreds of Venezuelans have since been removed from the U.S. under the Alien Enemies Act, which allows the president to expeditiously deport noncitizens during wartime.

Trump invoked this law after he claimed the gang was invading the United States. That justification is now the heart of dispute between Department of Justice lawyers and a federal judge.

But in assessing the use of tattoos as a main identifier of gang affiliation, Risquez pointed out that as in all parts of the world, the only way to determine that a person is a delinquent or criminal is “to conduct a police investigation” and “grant them due process.”