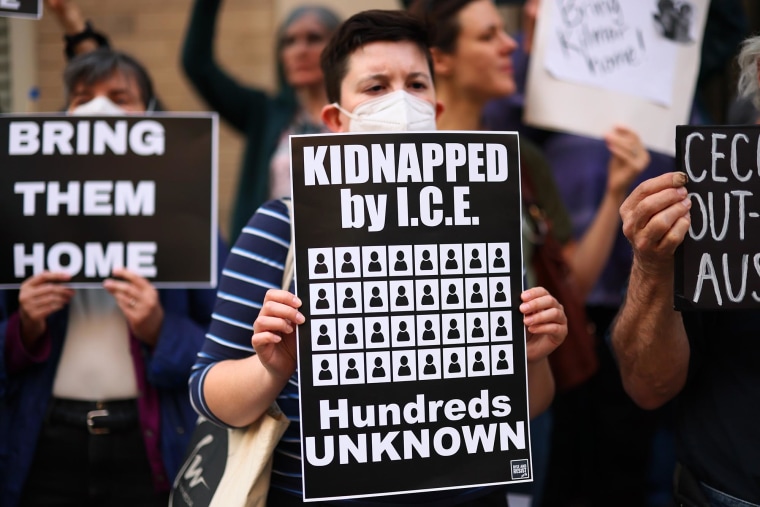

A deportation flight carrying immigrants to El Salvador took off while a judge was ruling in the case. A mother of two U.S. citizens was sent to Honduras without speaking to anyone other than immigration officials. College students have been suddenly arrested on city streets and sent to detention centers hundreds of miles away.

The Trump administration’s promise to carry out the biggest deportation campaign in American history has a distinct and potent hallmark: speed. Officials have fast-tracked deportation proceedings so that some people are removed without speaking to an attorney, family members or without a court hearing at all.

Trump’s immigration efforts have broken norms and bent the law as he enacts his agenda with dizzying fervor, seeking to show his supporters he’s delivering, even as the overall number of deportations in February lagged behind Biden administration during the same period last year.

“One theme that runs through all the Trump administration’s immigration actions this term is its attempt to rush people out of the country without due process or oversight by the courts,” said Lee Gelernt, a lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union, who has argued some of the most high-profile immigration-related challenges to Trump during both terms.

Trump’s first-term push to drastically reshape the nation’s immigration system was often stymied by the courts, slowed because of the officials around him or undone over a tide of public criticism. The president has been emboldened in his second term, surrounded by loyalists and governing a nation that has moved to the right on immigration.

“This is a much more powerful presidency than I had the first time,” Trump told The Atlantic in April. “The first time, I was fighting for survival and I was fighting to run the country. This time I’m fighting to help the world and to help the country.”

Even as Trump slams individual judges publicly, he and his aides have stressed that they will abide by court rulings. Still, administration officials are testing that line.

“I can’t — I can’t have a trial — a major trial — for every person that came in illegally,” Trump said this week in an interview with ABC.

In March, after Trump signed an executive order invoking the Alien Enemies Act — a rarely used wartime power — to deport men alleged to be members of a Venezuelan gang, a federal judge during an emergency hearing ordered deportation flights to be turned around.

But two planeloads of people were deported anyway, taken to a prison in El Salvador that has a history of human rights abuses. U.S. District Judge James Boasberg has since suggested that the deportations appeared to be designed to “outrun” the judicial system.

A federal judge Thursday ruled Trump could not rely on the act to detain and remove migrants.

White House officials argue that voters chose this agenda; Americans consistently reported immigration reform as a top priority. More than 100 days into his presidency, the issue still resonates but adults were split, with 49% approving of his handling of border security and immigration and 51% disapproving, according to an NBC News Stay Tuned Poll, powered by SurveyMonkey.

There is still a massive backlog of immigration cases, though Biden-era policies that allowed migrants to stay in the U.S. and work have been rescinded and asylum-seekers once again must wait for their cases across the border.

Trump’s team is seeking to fast-track deportation cases, so they don’t get bogged down this time by legal wrangling.

“You’re not going to get an ounce of sympathy from this administration or President Trump,” Stephen Miller, Trump’s deputy chief of staff and arbiter of immigration policies, said Thursday.

The administration has argued that it is not required to provide immigrants due process during arrest and deportation proceedings, citing rarely used provisions, including the Alien Enemies Act of 1789, said Muzaffar Chishti, director of the Migration Policy Institute at the NYU School of Law.

The minimal requirement for due process, as defined by judges over time, “is that you know what you are being charged for, you have the ability to present the case against the charge, and you have the right to have a lawyer to that,” he said.

By that definition, Chishti said, he doubted due process was met “in the speed with which they are executing these deportations.”

In a January interview with NBC News, Trump’s border czar, Tom Homan, acknowledged that the administration’s mass deportation plans would include “collateral arrests” — immigrants without criminal records who are discovered as Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents search for targets.

Homan said those with criminal records remain the priority, but anyone in the U.S. illegally should consider themselves a target. But some of these recent cases have involved undocumented immigrants arrested during a routine check-in with immigration officials, a significant escalation of the deportation efforts.

According to the Department of Homeland Security, immigration officers had arrested 151,000 undocumented immigrants, far more than the Biden administration did during the same period last year.

But overall deportations are lagging behind that of the Biden administration during the same period last year.

Trump officials say it’s because of a drastic drop in border crossings. But they’re looking to keep the pressure up in other ways — through brashness and high-profile arrests.

And unlike his first term, when after widespread condemnation, Trump backed off the “zero-tolerance policy” that separated families who crossed the border to seek asylum, there has been no backing down, even as some efforts draw criticism.

The administration has revoked more than 300 student visas; college students have been picked up, in some cases by masked immigration agents, and held in detention centers, sometimes a thousand miles from their homes with little warning and often with few details about why they were being detained.

And last week in Louisiana, three U.S. citizen children from two families were removed from the country with their mothers amid public outcry. One of them is a 4-year-old with stage 4 cancer who was being treated in the U.S.

Homan said Monday that officials sent the children because the mothers requested they depart with them. “This was a parental decision. Parenting 101. The mothers made that choice,” he said.

Yet, Sirine Shebaya, the executive director of the National Immigration Project, which has been helping on the cases, insisted the mothers did not choose to have their children removed from the U.S. and that they were given no other alternatives. She said they were not told that “there were people on the outside saying they were ready to take their kids with them.”

One of the women who was flown out with her 2-year-old U.S. citizen daughter is pregnant. Attorneys said she had a less than two-minute phone call with her husband that Immigration and Customs Enforcement abruptly cut off, so she could not arrange for her child to stay in the U.S. She had been in the country a number of years and checking in with ICE regularly, Shebaya said.

The second was deported with her 4-year-old son who has stage 4 cancer and her daughter, 7, both citizens. Attorneys said the boy was sent out without access to his medications and treatment. The woman’s attorney said she did not sign or write anything or give consent to her children being removed from the country with her. He said she wasn’t given a phone to call her attorney or family.

Shebaya said normally, there’s time for people who are ordered to be deported to make a case to stay, and it’s highly unusual when children are involved not to make time for decisions to be made about the children.

But both women had been ordered to be deported after they failed to show for immigration appointments, making them targets for a faster deportation.

The mother with the 2-year-old missed her appointment because she had been kidnapped while waiting in Mexico, said Mich P. González, co-founder of Sanctuary of the South, an immigration and LGBTQ civil rights cooperative, who represents her. She was eventually released. The second woman, who had been an unaccompanied minor at 13 and claimed asylum at the border, didn’t receive the notice for a hearing, González said.

The administration is also ramping up its calls for undocumented immigrants to leave voluntarily — or risk being permanently barred from the country if immigration authorities find them first.

Tricia McLaughlin, a spokesperson for the Department of Homeland Security, said the administration has given parents in the U.S. illegally the opportunity “to take control of their departure process with the potential ability to return the legal, right way and come back to live the American dream.”

Linda Rivas, an immigration lawyer in El Paso, Texas, summed up the second-term agenda this way: “Law feels like a suggestion. Families and communities are terrified of what’s to come.”