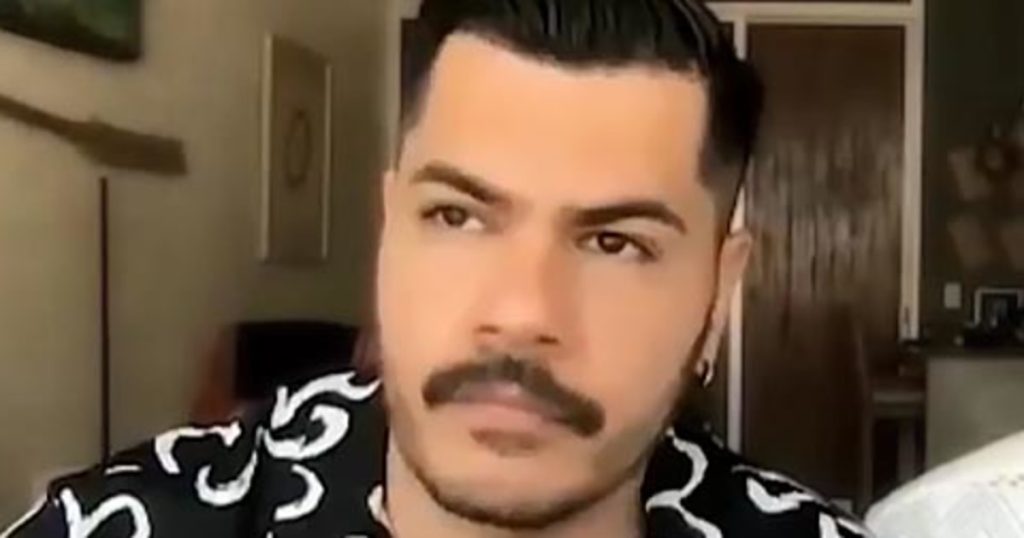

Despite his undocumented status, Francisco Hernandez-Corona, 34, and his U.S. citizen husband, Irving Hernandez-Corona, never thought they would leave the United States. But the new administration changed all that when it came in in January, according to the couple.

“We started seeing ICE everywhere and people sent to El Salvador,” said Francisco.

“There would be knocks at the door and he (Francisco) would be scared and be terrified,” said Irving. “It was never our intention to leave under these circumstances. We left, basically fleeing.”

They fled to Mexico’s west coast, flying into Puerto Vallarta three weeks ago, where they say they finally felt safe and wanted.

“(Mexicans) all were saying, ‘Welcome back home! You belong here,’” said Francisco.

The warm welcome was greatly appreciated, but they still felt sad leaving behind their family in the United States.

“We still sit here in silence sometimes, hold each other and cry because of what we left,” said Irving. “We felt pushed out.”

The couple had just celebrated a milestone — married last fall after three years of dating.

Francisco graduated from Harvard, where he studied clinical psychology and graduated in 2013. It had not been an easy road to get there.

When he was only 10 years old, Francisco’s father arranged for him to cross into the U.S. through the desert with a “coyote,” or migrant smuggler. “The worst three days of my life, I remember every moment walking through the desert,” he said. “Nobody asked me if this is what I want to do. I didn’t have a choice.”

His family settled in Lennox, a small city near the airport in Los Angeles. Francisco excelled in school and was accepted to Harvard in 2009. Around that time, he was hit with another challenge.

“My mom died my senior year of high school,” said Francisco.His mother lost her battle with a rare disease just months before he graduated.

His younger sister moved to live with his older, adult sister in Texas, but Francisco stayed and was taken in by his teachers, who saw him through graduation and into an Ivy League education.

“I made it. This little, brown boy from Lennox is going to Harvard, that’s crazy,” Francisco said.

In 2012, he applied for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, under President Obama, which does not grant legal immigration status but allows young undocumented immigrants who qualify to live and work in the U.S.

He later didn’t renew DACA since he filed for a Violence Against Women (VAWA) visa; he and his mom were victims of abuse by his dad, he said, adding his parents had divorced. But Francisco said processing of the VAWA visas have been delayed by more than a decade. And because he technically re-entered the country illegally when he was forced to cross the border at 10 — his mom had brought him on a tourist visa when he was 6 and she had overstayed their visit — Francisco was told he’d be barred from returning to the U.S.

“Because of the choice my dad made when I was a child, U.S. law says it doesn’t matter. I don’t care that you were 10, I don’t care if you were bleeding in the desert, or crying in the desert alone. I don’t care that you didn’t choose this; you can no longer stay in a place that you call home,” said Francisco.

After marrying Irving last year, he thought there might be a way to fix his status but his attorneys instead recommended they cancel their honeymoon to Puerto Rico, fearing Francisco might be detained at some point. That’s when the couple decided to self-deport.

“That’s when I looked at him and said, ‘Then, I guess we have to leave,’” said Francisco. “There isn’t any reason for us to stay here.”

“It’s such a hateful place, a hateful environment,” said Irving.

Now living in Mexico, they are trying to figure out the next steps and are grateful to still be working remote jobs from the U.S.

Francisco hopes to visit the Mexican grave where his mother was interred after she died in Los Angeles. He has never seen it in person, but worries that he will feel guilt that he failed to fulfill his dying mother’s wish.

“She said, ‘I will die here so that you and your sisters could have a better life, so that you and your sisters could have the life that I’ve never had,’” he said.

Francisco said he hopes one day to come to return to the United States, raise children with Irving and hopefully send them to Harvard.